Overall Impact

Armenia lies in a seismic zone that stretches from Turkey to India, where the Arabian tectonic plate pushes north, colliding with the Eurasian plate. Historically, this fault line formed the Caucasus mountain system and is responsible for centuries’ worth of seismic activity.

On December 7th, 1988, at 11:41 am, the first tremor of a powerful earthquake struck northern Armenia, its epicenter approximately three miles away from the town of Spitak. It was recorded at 6.8 on the Richter magnitude scale. Four minutes later, an aftershock of 5.8 intensity hit. Over the next year, hundreds of much smaller aftershocks were recorded by geologists.

The earthquake’s destruction impacted the country in a severe and lasting manner. It destroyed 21 towns and 342 villages, spreading over roughly 40% of Armenia’s total land area.[1] Many buildings partially left standing after the first tremor were totally leveled by the second. This represents approximately 8 million square meters of lost housing, up to 17% of the country’s entire housing stock at the time.[2] As many as 30,000 people were killed and 150,000 injured, while over 500,000 were left without shelter.[3] The resulting chaos drove a great number of people to relocate: it’s estimated that 130,000 individuals were evacuated from the country and some 150,000 migrated to Yerevan from the crippled north.[4] Economically speaking, the total cost of the earthquake has been estimated at $10 billion USD[5], and it reduced Armenia’s productive capacity by about 40 percent.[6] The quake interrupted essential services such as communication, transport, water, sanitary, and energy supply lines that were haphazardly rebuilt over the difficult decade that followed.

The situation in the immediate aftermath was perilous, and it was exacerbated by inefficiency, corruption, and competition for relief aid. Survivors were in shock. Neither they nor the rescue workers were properly equipped to deal with the cold. At first, rescue work was done by hand and with home tools until technical equipment arrived, although so few cranes were brought that manual labor was still the primary method of rescue. Doctors worked to stabilize the injured; there were too many people hurt, too severely, to pay significant attention to a single individual. Looters stole from corpses and preyed upon the weak and elderly. Translation problems added to the disorder. Some relief materials never reached their intended destination, instead stolen or redirected, or were even sold on the streets of Yerevan, according to some reports.[7] Temporary housing erected for the homeless was small, cramped, and offered little protection from the elements.

Local Impacts

Spitak

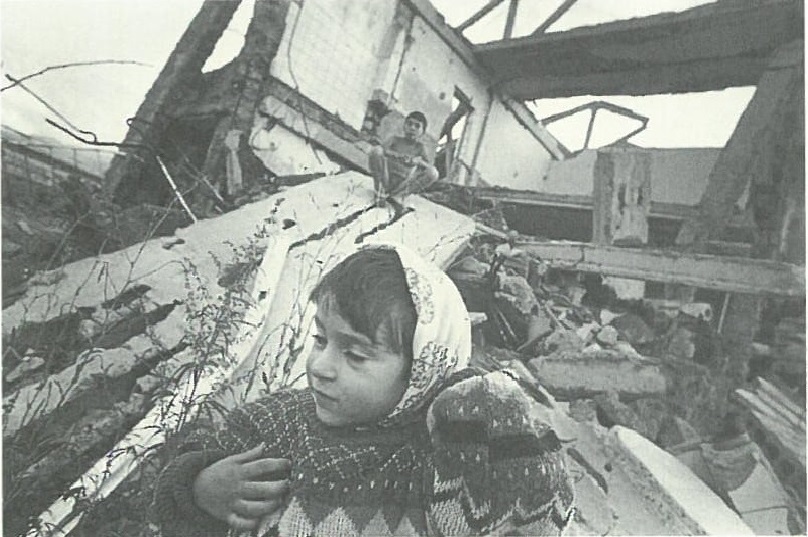

Girl in front of her destroyed school in Spitak. Picture by Jerry Berndt.

Possibly the greatest effects of the earthquake were felt in Spitak. All major structures were destroyed. Soviet authorities were aware that the area was a seismic zone and had considered earthquake resistance in local construction, but the combined strength of the first shock and the aftershock surpassed their preparations. Furthermore, flawed construction practices and some design choices meant that not all buildings were built fully agreeing with Soviet code, much less international standards. Stone buildings collapsed into rubble, straight down, trapping people inside. Of its pre-earthquake population of 25,000, it’s estimated that around 5,000 people died in Spitak alone.[8]

Many different countries contributed to rebuilding Spitak by constructing a particular neighborhood or civic building. For example, the Norwegians built a hospital and housing for doctors, the Italians set up small, prefabricated housing units, and the Swiss, together with Armenian workers, built a large neighborhood of family homes. New construction was built to withstand a greater degree of seismic stress. The combined effort of these countries left a multinational imprint on Spitak still visible today: structures built by Russians, Uzbeks, Estonians, Norwegians, Italians, and Swiss workers are referred to using those international monikers in the present. These neighborhoods were built concurrent with the clean-up of debris, in separate locations. Local residents were sometimes, but not always, consulted about where new construction should go. Many of the square, squat temporary houses have since been augmented and renovated by the families who continue to live there, in ingenious and creative ways.

Some of the adaptations necessary in that moment became unique, distinctive features of today’s Spitak. In the immediate aftermath, a church built entirely of sheet metal was erected in memorial, important for those who found comfort in faith. Although later a traditional stone church was built in the new downtown, the metal one can be seen from the highway as you drive toward the city center. It remains unique in the material and circumstances of its construction. Also, a center was established by the Missionaries of Charity - the order founded by Mother Teresa - to help the suddenly larger population of Spitak residents with various mental or physical disabilities. It still operates today and hosts sisters from all over the world.

Gyumri & Elsewhere

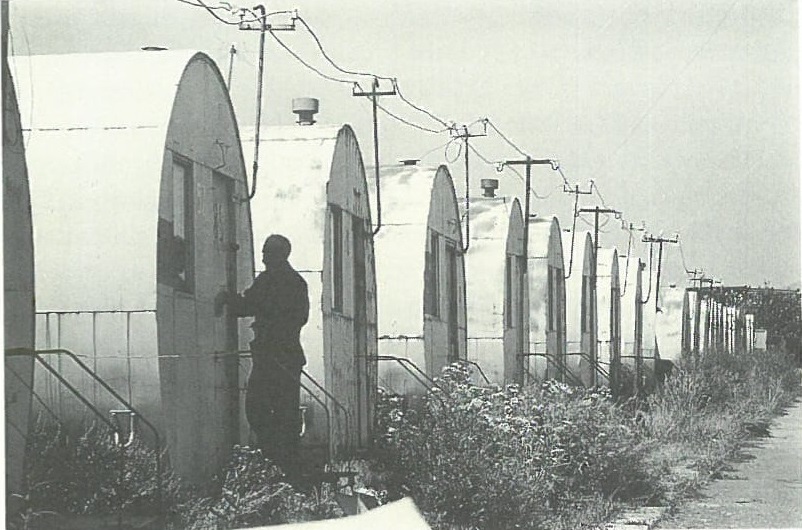

After the earthquake many lived in Domiks like these in Gyumri. Picture by Jerry Berndt.

After Spitak, the most severe effects of the 1988 earthquake were felt in Gyumri, then known as Leninakan, Armenia’s second-largest city. At the time, the population was around 200,000, of which there were an estimated 15,000-17,000 fatalities.[9] About 80% of structures there were destroyed, primarily large apartment blocks built in the late Soviet era.[10] Between Spitak and Gyumri, 105 of the 131 schools were unusable.[11] Gyumri, though farther from the epicenter than Vanadzor, suffered more damage due to its geographical location within a wide, elevated plain as opposed to being encircled by mountains.

The Soviet government’s response was delayed and evaded direct responsibility for the poor quality construction that collapsed. In addition, Soviet officials delayed giving permission for foreign aid workers to enter the city, and ten days after the quake decreed that all foreigners should leave. In total, at least 24,000 homes were destroyed, and families still live in temporary housing in several neighborhoods of Gyumri.[12]

This video depicts the earthquake aftermath in Gyumri, and this documentary provides further images and personal testimony.

The towns of Vanadzor and Stepanavan were also partially destroyed. On our Stories page you can learn more about the impact on those cities, as well as the impact on some smaller northern villages.

Snapshot of the 1988 Armenian Earthquake

Strength of the Earthquake: 6.8

Death Toll: 25,000 - 50,000

Villages Destroyed: 342

Total People displaced: 500,000

Percent of Armenian Territory Affected: 40%

Estimated Cost of the Earthquake: 10 Billion USD

International Response

A swift and substantial international relief response followed. Overall, an estimated 1500 rescue workers and 230 physicians came to Armenia. The Red Cross brought relief materials from countries across Western and Eastern Europe. Many other countries with no diplomatic relations with the USSR came to help like Israel, South Korea, Chile, and South Africa. By July 1989, the donations amounted to an estimated $500 million USD from 113 countries.[13]

Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev with President Reagan and Vice-President Bush before finding out about the earthquake.

Notably, the international response was the first occasion since World War II in which the U.S. and other European nations were permitted to officially enter a Soviet republic. When the earthquake struck, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev was actually in the United States, partaking in a landmark meeting with American President Ronald Reagan. The next day, Gorbachev flew back to Moscow to address the situation. He initially pledged 5 billion rubles (currently about $8 billion US dollars) to the relief effort, but due to several major obstacles, such as the fall of the USSR, that amount never reached the victims.[14] This is sometimes referred to as the “fall of the humanitarian wall,” marking a new phase in humanitarian history, because the international community broadly participated in disaster relief in spite of Cold War political tensions.

Despite its status as the governing power of a vast welfare state and its rule over Armenia, the Soviet Union’s response to the earthquake was inconsistent at best and obstructive at worst. Foreign aid workers and journalists arriving in Moscow were delayed by Soviet bureaucratic inefficiency and outright suspicion. When Armenian civilian bureaucracy also proved ill-equipped for an effective response, state press viciously criticized them. Soviet doctors were inexperienced in dealing with the extensive cases of “crush syndrome,” so specialized medical equipment and personnel trained in treating internal organ damage were flown in from abroad. When the Soviet Union disintegrated, so did the relief work it supported, and promised reconstruction projects were abandoned.

French rescuer with a dog searching through the rubble. Photo by Alexander Makarov.

Despite its shortcomings, the volume and vigor of the international aid response is undeniable. Volunteers who helped at the time now estimate that 80 percent of the supplies were distributed fairly.[15] Government officials, 16 years afterwards, estimated that a total of $2 billion in foreign aid was delivered.[16]

Internationally, the response to the 1988 Armenian earthquake taught new lessons for humanitarian mobilization. Until the late 1980s, most international disaster relief work had responded to emergencies in tropical areas. Delivering humanitarian aid in a cold-weather environment, in the middle of winter, presented different challenges. Protection from the winter, in the form of shelter and warm clothes, was as urgent a need as clean water, medical care, and food. Rescue teams trying to evacuate victims in the bitter cold realized that their own winter protection needs mattered too. Thus, the experience offered lessons for responding to future disasters, focusing more attention on the unique challenges of cold-weather rescue operations. Similar lessons were learned in regard to gender inclusivity - as more warm clothing for men was donated than for women and children - and language inclusivity, because much of the writing on delivered materials was in languages other than Russian or Armenian, which required time and expertise to translate.

Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh

Escalating tensions over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh took place concurrently with the earthquake and relief effort, shaping the lives of many Armenians at the time.

The region of Nagorno-Karabakh is a semi-autonomous republic internationally recognized as Azerbaijani territory, although governed by and populated by a nearly 95 percent ethnic Armenian population of the total 146,000 inhabitants.[17] Situated between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh comprises a land mass about a sixth of Armenia’s size and a tenth of Azerbaijan's. Armenians often refer to Nagorno-Karabakh using an Armenian designation, Artsakh.

The region was forcibly placed under Azerbaijani rule in 1921 by Joseph Stalin, when the nascent Soviet government in Moscow began partitioning its empire. It remained a part of the Azerbaijani Socialist Soviet Republic until the collapse of the USSR. In the late 1980s, however, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s moderate policies of glasnost and perestroika provided a historic opportunity for the Armenians of Karabakh to express their grievances and demand reunification with the homeland. Thus began a mass nationalist movement in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh from 1988 to 1992 seeking Armenian jurisdiction over the region.

Stepanakert

Mass protests began in early 1988 in Yerevan and Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital Stepanakert, demanding the Soviet government unite the two territories. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators gathered in Yerevan on several occasions during the year.

Protests intensified later in 1988, as violent clashes developed between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in Stepanakert. The Azerbaijani government began mass expulsions of Armenians in November, followed by the mass emigration of Azerbaijanis leaving Armenia. The Russian TASS news agency later placed the number of victims during 1988 in Azerbaijan and Armenia at 91 dead and 1,650 injured.[18]

The first demonstrations of the Karabakh movement in Stepanakert on February 13th, 1988.

After the December 7th earthquake, protestors gathered in Yerevan following rumors that the Soviet government was moving large numbers of orphans from Armenia to Russia. These demonstrations quickly grew over anger that Soviet authorities had arrested leaders of the Karabakh Committee, the main organizers of the reunification movement. Unsatisfied with his lack of results, public pressure forced the resignation of Karen Demirchyan, the leader of the Armenian SSR. The next year, in December 1989, the Supreme Soviets of the Armenian SSR and the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region (the local leadership) passed a resolution on the formal unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia. In 1991, both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh declared independence.

Violence continued to escalate as the Soviet Union weakened. In an effort to maintain stability, Soviet authorities relocated several thousand Armenians from Karabakh’s villages to its capital with the assistance of Azerbaijani forces. Armenians began to arm and sent thousands of soldiers to Karabakh. Formal battles between the newly independent Armenian and Azerbaijani militaries ensued, and by 1992 the fighting developed into a full-scale war.[19]

From 1914 to 2018: A Walk Through Armenia’s Past

Challenges after Independence

After achieving its independence, residents of the entire country endured a difficult period due to the combined troubles of the earthquake, the war over Karabakh, and the challenges of a new country. The nation struggled through an economic crisis, searching for ways to provide sufficient food and energy to meet the needs of its people.

A women burns a piece of tire in Yerevan to keep warm. Picture by Jerry Berndt.

The sudden transition from being a member of a large, communist collective of states to a small, independent country upended people’s lives. All of the Soviet republics were economically interdependent, each one relying on the resources and products from the others for their economic contribution to the whole. Upon Armenia’s independence, old Soviet factories closed and the economy ground to a halt. Unemployment dramatically rose. While families in rural areas could earn income from farming, the only available industry for urban residents was trading: household items were bought and sold for prices much lower than their original worth. The market was dominated by sellers; there were few buyers. Locally owned businesses didn’t have regular access to electricity to operate, and artisans didn’t have necessary raw materials to create.

A bread ration was started, and people were accustomed to waiting all day in line. The bread deliveries themselves arrived inconsistently. All this led many to conclude that the only way to make a living was working outside of Armenia and sending money home. A substantial number of educated professionals left to seek better fortunes abroad, creating a brain drain for the newly independent state. Others who stayed could be found bartering in the market, with no opportunity to use their expertise from what felt like a previous life. Some Armenians despaired, without a job or active purpose to busy themselves. International aid sometimes helped families, but the aid itself didn’t generate any income or kickstart economic activity. Begging became common on the streets of Yerevan.

These difficulties caused dramatic changes in the home lives of families, shocks to the Armenian way of life. Food was eaten cold rather than heated. Coffee, a ubiquitous cultural staple offered to guests, became expensive and therefore scarce, so many families stopped hosting guests for the embarrassment of not being able to offer a gesture of goodwill. Meat became an expensive luxury. Armenian families normally prepared for the winter by saving abundant summer fruit in the form of jams, preserves, and compotes, but now didn’t have the money for canning. Overall, priorities were shifted toward present urgencies, for securing sufficient food for the family today.

A grandmother and grandson collect fuel in Yerevan. Picture by Jerry Berndt.

Cultural activities such as theatre and music still took place in Yerevan, portraying celebrated Armenian works, but they were no longer affordable, except for occasions of events free to the public. Bread was the daily focus, and people went without new clothes or even medication to instead spend their money on food. Conducting traditional life cycle events like childbirth, weddings, and funerals put enormous financial strain on families.

Due to the coincidence of the earthquake and the Karabakh war, a severe energy crisis emerged from the fallout. For fear of a Chernobyl-like disaster, in February 1989 the Armenian government closed Metsamor, the Armenian nuclear power plant, following the quake but before the Turkish and Azerbaijani fuel blockade. The lack of electricity slowed the economy and society. Yerevan residents were limited to less than two hours of electricity a day by the winter of 1994-1995.[20] People adjusted, waking up at odd hours to perform household chores while there was power. The plant was not reactivated until 1995, despite public pressure. This meant heating was another serious expense in addition to food. People burned books and old furniture to stay warm. They blocked off unused sections of the house to congregate in one area, wore several layers of clothing, and simply lingered long in bed. Wood was precious, which encouraged people to cut and uproot Armenia’s trees, leading to significant deforestation of the northern regions.

“Family networks were shattered, and familiar hometown landscapes were transformed.”

Lasting Legacy

The years after the earthquake held complex psychological, economic, and cultural consequences for those in the affected regions. As the earthquake happened during the day, while people were engaged in their normal routines, many have distinct memories of where and what they were doing at the time. Family networks were shattered, and familiar hometown landscapes were transformed. Children and adults suffered from what is now recognized as undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder. Beyond losing houses as physical structures, people lost a sense of safety and security in their homes. Many churches were destroyed, a significant blow to a nation that proudly defines itself as Christian. Families faced many unmet needs and felt unsupported after the distribution of aid ended, even as help continued to come from other regions of Armenia.

Border to Border, a project that involves American and Armenian volunteers teaching about healthy living passes by a church being renovated.

Economically, these regions faced serious obstacles to rebuilding. Much infrastructure and productive capacity was destroyed, services not easy to replace in a new country. The recovery was further delayed by the Turkish boycott, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the subsequent war over Karabakh. At the time, many Armenians wished that international aid would include machinery and systems to lay the foundation for future economic growth.

As people left looking for jobs, the depopulation of northern Armenia accelerated. The forces that pushed people to leave were numerous: the cold and hunger, inconsistent political leadership, and the idea that going abroad to join already-established diaspora communities would not make them any less “Armenian”.[21] Others remained out of obligation to their country and neighbors, or because they didn’t have the financial means to leave. Of the population that left, some returned to Armenia, but many settled into new lives abroad. A portion of that population stopped sending money home, leaving their relatives unsupported and adrift. Today, many men from the northern regions still seek work abroad in Russia or elsewhere because of the economic situation, whether moving permanently or engaging in seasonal labor for part or most of the year.

A memorial for the 1988 Armenian earthquake in Spitak.

Since 1988, the earthquake has found its place in popular culture. Shortly afterwards, the French-Armenian singer Charles Aznavour created the song “Pour toi Arménie” (For you, Armenia), to focus international recognition on the victims and raise relief money. He also established a foundation, “Aznavour pour l’Arménie”, a charity fund which gave millions of dollars in assistance to earthquake survivors. Over the next decade, the foundation provided basic necessities like homes, food, and electricity for thousands of Armenians struggling during the early Republic’s difficult years. For his humanity - visiting Armenia, spending time with survivors, and organizing this foundation - he is recognized as an Armenian hero today.

A more contemporary musical recognition of the event is Tigran Hamasyan’s haunting piano composition Leninagone. The official video for this song depicts a year-end musical performance from Hamasyan’s 1995 second-grade class in Gyumri, who were studying in a temporary school at the time.

The earthquake’s impact has been further memorialized in films such as Earthquake (2016), which follows the intersecting stories of disparate survivors in Gyumri, and the recent Spitak (2018), which follows a man named Gor as he returns from Moscow to Spitak to find his family.

Further Reading

The history of the Armenian people is complex. While we focus here on what’s necessary to understand the historical impact of the earthquake, there’s much more to learn. The following historical works can answer your questions about the Armenian genocide, the conflict over Karabakh, the Soviet Union, and more:

The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, Richard Hovhannisian (two volumes, 1997)

Survivors: An Oral History of the Armenian Genocide, Donald E. Miller and Lorna Touryan Miller (1999)

Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope, Donald E. Miller and Lorna Touryan Miller (2003)

Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War, Thomas de Waal (2003)

The Hundred Year Walk: An Armenian Odyssey, Dawn Anahid Mackeen (2016)

Citations & Bibliography

[1] https://armeniasputnik.am/infographics/20161207/5709122/armenia-erkrasharj-spitak.html

[2] Vahanyan, Grigori. "Telehumanism" (30 Years after Spitak Earthquake December 7, 1998). Lambert Academic Publishing, 2018.

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] https://literatur.thuenen.de/digbib_extern/dn056911.pdf

[6] https://armeniasputnik.am/infographics/20161207/5709122/armenia-erkrasharj-spitak.html

[7] Vahanyan, Grigori. "Telehumanism" (30 Years after Spitak Earthquake December 7, 1998). Lambert Academic Publishing, 2018.

[8] Miller, Donald E, and Lorna Touryan Miller. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. University of California Press, 2003.

[9] http://www.nssp-gov.am/spitak_eng.htm

[10] https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/earthquakes-wreak-havoc-in-armenia

[11] Miller, Donald E, and Lorna Touryan Miller. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. University of California Press, 2003.

[12] https://www.rferl.org/a/1088188.html

[13] Vahanyan, Grigori. "Telehumanism" (30 Years after Spitak Earthquake December 7, 1998). Lambert Academic Publishing, 2018.

[14] https://www.mcclatchydc.com/latest-news/article24443344.html

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] https://web.archive.org/web/20090327083447/http://www.stat-nkr.am/2000_2006/05.pdf

[18] https://www.evnreport.com/spotlight-karabakh/karabakh-movement-88-a-chronology-of-events-on-the-road-to-independence

[19] de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN9780814719459.

[20] https://oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Nuclear-Power/Armenias-Aging-Metsamor-Nuclear-Power-Plant-Alarms-Caucasian-Neighbors.html

[21] Miller, Donald E, and Lorna Touryan Miller. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. University of California Press, 2003.

Charles Kelly (2002) Cold weather: an unrecognized challenge for humanitarian assistance, Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards, 4:2, 79-81, DOI: 10.3763/ehaz.2002.0408

de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814719459.

“Karabakh Movement 88: A Chronology of Events on the Road to Independence.” EVN Report, EVN Report, 26 Feb. 2018, www.evnreport.com/spotlight-karabakh/karabakh-movement-88-a-chronology-of-events-on-the-road-to-independence.

Lessons and Questions Emerge from Armenian Quake Author(s): Richard Monastersky Source: Science News, Vol. 135, No. 3 (Jan. 21, 1989), p. 43 Published by: Society for Science & the Public Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3973507 Accessed: 13-10-2018 11:12 UTC

Miller, Donald E, and Lorna Touryan Miller. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. University of California Press, 2003.

Vahanyan, Grigori. "Telehumanism" (30 Years after Spitak Earthquake December 7, 1998). Lambert Academic Publishing, 2018.